Difference between revisions of "Aristotle"

(Created page with 'File:lighterstill.jpgright|frame '''Aristotle''' is a towering figure in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_Philosophy ancient Greek p...') |

m (Text replacement - "http://" to "https://") |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

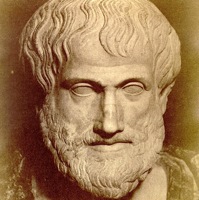

[[File:lighterstill.jpg]][[File:Aristotle-face-1.jpg|right|frame]] | [[File:lighterstill.jpg]][[File:Aristotle-face-1.jpg|right|frame]] | ||

| − | '''Aristotle''' is a towering figure in [ | + | '''Aristotle''' is a towering figure in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_Philosophy ancient Greek philosophy], making contributions to [[logic]], metaphysics, [[mathematics]], [[physics]], [[biology]], botany, [[ethics]], [[politics]], agriculture, medicine, dance and theatre. He was a student of [[Plato]] who in turn studied under [[Socrates]]. He was more empirically-minded than Plato or Socrates and is famous for rejecting Plato’s theory of forms. |

| − | As a prolific [[writer]] and polymath, Aristotle radically [[transformed]] most, if not all, areas of [[knowledge]] he touched. It is no wonder that [[Aquinas]] referred to him simply as “The Philosopher.” In his lifetime, Aristotle wrote as many as 200 treatises, of which only 31 survive. Unfortunately for us, these works are in the form of [[lecture]] notes and draft manuscripts never intended for general readership, so they do not demonstrate his reputed polished [[prose]] style which attracted many great followers, including the Roman [ | + | As a prolific [[writer]] and polymath, Aristotle radically [[transformed]] most, if not all, areas of [[knowledge]] he touched. It is no wonder that [[Aquinas]] referred to him simply as “The Philosopher.” In his lifetime, Aristotle wrote as many as 200 treatises, of which only 31 survive. Unfortunately for us, these works are in the form of [[lecture]] notes and draft manuscripts never intended for general readership, so they do not demonstrate his reputed polished [[prose]] style which attracted many great followers, including the Roman [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero Cicero]. Aristotle was the first to classify areas of human knowledge into distinct disciplines such as mathematics, biology, and ethics. Some of these classifications are still used today. |

| − | As the father of the field of [[logic]], he was the first to develop a formalized system for reasoning. Aristotle observed that the validity of any [[argument]] can be determined by its [[structure]] rather than its [[content]]. A classic example of a valid argument is his syllogism: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal. Given the structure of this argument, as long as the premises are true, then the conclusion is also guaranteed to be true. Aristotle’s brand of logic dominated this area of [[thought]] until the rise of modern [ | + | As the father of the field of [[logic]], he was the first to develop a formalized system for reasoning. Aristotle observed that the validity of any [[argument]] can be determined by its [[structure]] rather than its [[content]]. A classic example of a valid argument is his syllogism: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal. Given the structure of this argument, as long as the premises are true, then the conclusion is also guaranteed to be true. Aristotle’s brand of logic dominated this area of [[thought]] until the rise of modern [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propositional_logic propositional logic] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predicate_logic predicate logic] 2000 years later. |

Aristotle’s emphasis on good reasoning combined with his [[belief]] in the [[scientific method]] forms the backdrop for most of his work. For example, in his work in [[ethics]] and [[politics]], Aristotle identifies the highest good with [[intellectual]] [[virtue]]; that is, a moral person is one who cultivates certain virtues based on reasoning. And in his work on [[psychology]] and the [[soul]], Aristotle distinguishes sense [[perception]] from [[reason]], which unifies and interprets the sense perceptions and is the source of all knowledge. | Aristotle’s emphasis on good reasoning combined with his [[belief]] in the [[scientific method]] forms the backdrop for most of his work. For example, in his work in [[ethics]] and [[politics]], Aristotle identifies the highest good with [[intellectual]] [[virtue]]; that is, a moral person is one who cultivates certain virtues based on reasoning. And in his work on [[psychology]] and the [[soul]], Aristotle distinguishes sense [[perception]] from [[reason]], which unifies and interprets the sense perceptions and is the source of all knowledge. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Aristotle famously rejected [[Plato]]’s theory of forms, which states that properties such as [[beauty]] are [[abstract]] universal entities that exist independent of the objects themselves. Instead, he argued that forms are [[intrinsic]] to the objects and cannot exist apart from them, and so must be studied in [[relation]] to them. However, in discussing art, Aristotle seems to reject this, and instead argues for idealized universal form which artists attempt to capture in their work. | Aristotle famously rejected [[Plato]]’s theory of forms, which states that properties such as [[beauty]] are [[abstract]] universal entities that exist independent of the objects themselves. Instead, he argued that forms are [[intrinsic]] to the objects and cannot exist apart from them, and so must be studied in [[relation]] to them. However, in discussing art, Aristotle seems to reject this, and instead argues for idealized universal form which artists attempt to capture in their work. | ||

| − | Aristotle was the founder of the [ | + | Aristotle was the founder of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyceum Lyceum], a school of learning based in Athens, Greece; and he was an [[inspiration]] for the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peripatetic_school Peripatetics], his followers from the Lyceum.[https://www.iep.utm.edu/aristotl/] |

[[Category: Philosophy]] | [[Category: Philosophy]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:41, 12 December 2020

Aristotle is a towering figure in ancient Greek philosophy, making contributions to logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance and theatre. He was a student of Plato who in turn studied under Socrates. He was more empirically-minded than Plato or Socrates and is famous for rejecting Plato’s theory of forms.

As a prolific writer and polymath, Aristotle radically transformed most, if not all, areas of knowledge he touched. It is no wonder that Aquinas referred to him simply as “The Philosopher.” In his lifetime, Aristotle wrote as many as 200 treatises, of which only 31 survive. Unfortunately for us, these works are in the form of lecture notes and draft manuscripts never intended for general readership, so they do not demonstrate his reputed polished prose style which attracted many great followers, including the Roman Cicero. Aristotle was the first to classify areas of human knowledge into distinct disciplines such as mathematics, biology, and ethics. Some of these classifications are still used today.

As the father of the field of logic, he was the first to develop a formalized system for reasoning. Aristotle observed that the validity of any argument can be determined by its structure rather than its content. A classic example of a valid argument is his syllogism: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal. Given the structure of this argument, as long as the premises are true, then the conclusion is also guaranteed to be true. Aristotle’s brand of logic dominated this area of thought until the rise of modern propositional logic and predicate logic 2000 years later.

Aristotle’s emphasis on good reasoning combined with his belief in the scientific method forms the backdrop for most of his work. For example, in his work in ethics and politics, Aristotle identifies the highest good with intellectual virtue; that is, a moral person is one who cultivates certain virtues based on reasoning. And in his work on psychology and the soul, Aristotle distinguishes sense perception from reason, which unifies and interprets the sense perceptions and is the source of all knowledge.

Aristotle famously rejected Plato’s theory of forms, which states that properties such as beauty are abstract universal entities that exist independent of the objects themselves. Instead, he argued that forms are intrinsic to the objects and cannot exist apart from them, and so must be studied in relation to them. However, in discussing art, Aristotle seems to reject this, and instead argues for idealized universal form which artists attempt to capture in their work.

Aristotle was the founder of the Lyceum, a school of learning based in Athens, Greece; and he was an inspiration for the Peripatetics, his followers from the Lyceum.[1]