Difference between revisions of "Corollary"

m (Text replacement - "http://nordan.daynal.org" to "https://nordan.daynal.org") |

m (Text replacement - "http://" to "https://") |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Origin== | ==Origin== | ||

| − | [https://nordan.daynal.org/wiki/index.php?title=English#ca._1100-1500_.09THE_MIDDLE_ENGLISH_PERIOD Middle English] ''corolarie'', from Late Latin ''corollarium'', from [[Latin]], [[money]] paid for a garland, gratuity, from [ | + | [https://nordan.daynal.org/wiki/index.php?title=English#ca._1100-1500_.09THE_MIDDLE_ENGLISH_PERIOD Middle English] ''corolarie'', from Late Latin ''corollarium'', from [[Latin]], [[money]] paid for a garland, gratuity, from [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corolla_%28chaplet%29 corolla] |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/14th_century 14th Century] |

==Definitions== | ==Definitions== | ||

*1: a [[proposition]] inferred [[immediately]] from a proved proposition with little or no additional [[proof]] | *1: a [[proposition]] inferred [[immediately]] from a proved proposition with little or no additional [[proof]] | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

:b : something that incidentally or naturally accompanies or [[parallels]] | :b : something that incidentally or naturally accompanies or [[parallels]] | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | In [[mathematics]] a '''corollary''' typically follows a [ | + | In [[mathematics]] a '''corollary''' typically follows a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theorem theorem]. The use of the term ''corollary'', rather than [[proposition]] or theorem, is intrinsically [[subjective]]. Proposition B is a corollary of proposition A if B can readily be [[deduced]] from A or is self-evident from its [[proof]], but the [[meaning]] of readily or self-evident varies depending upon the [[author]] and [[context]]. The importance of the corollary is often considered secondary to that of the initial theorem; B is unlikely to be termed a corollary if its mathematical [[consequences]] are as significant as those of A. Sometimes a corollary has a [[proof]] that explains the derivation; sometimes the derivation is considered to be self-evident. |

| − | In [[medicine]], corollary sometimes refers to using older, more narrow [[spectrum]] [ | + | In [[medicine]], corollary sometimes refers to using older, more narrow [[spectrum]] [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antibiotic antibiotics] whenever possible. This is to avoid an increase in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_resistance drug resistance]. |

*Peirce on corollarial and theorematic reasonings | *Peirce on corollarial and theorematic reasonings | ||

| − | [ | + | [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sanders_Peirce Charles Sanders Peirce] held that the most important division of kinds of [[deductive]] reasoning is that between corollarial and theorematic. He [[argued]] that, while finally all [[deduction]] depends in one way or another on mental [[experimentation]] on schemata or diagrams, still in corollarial deduction "it is only [[necessary]] to [[imagine]] any case in which the premisses are true in order to [[perceive]] immediately that the conclusion holds in that case," whereas theorematic deduction "is deduction in which it is necessary to [[experiment]] in the [[imagination]] upon the image of the premiss in order from the result of such experiment to make corollarial deductions to the [[truth]] of the conclusion." He held that corollarial deduction matches [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle Aristotle]'s conception of direct [[demonstration]], which Aristotle regarded as the only thoroughly [[satisfactory]] demonstration, while theorematic deduction (A) is the kind more prized by [[mathematicians]], (B) is peculiar to mathematics,[1] and (C) involves in its course the introduction of a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lemma_(mathematics) lemma] or at least a definition uncontemplated in the thesis (the [[proposition]] that is to be proved); in remarkable cases that definition is of an abstraction that "ought to be supported by a proper postulate.". |

[[Category: Logic]] | [[Category: Logic]] | ||

[[Category: Mathematics]] | [[Category: Mathematics]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:42, 12 December 2020

Origin

Middle English corolarie, from Late Latin corollarium, from Latin, money paid for a garland, gratuity, from corolla

Definitions

- 1: a proposition inferred immediately from a proved proposition with little or no additional proof

- 2a : something that naturally follows : result

- b : something that incidentally or naturally accompanies or parallels

Description

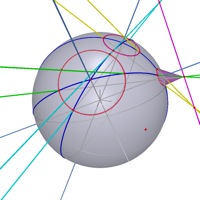

In mathematics a corollary typically follows a theorem. The use of the term corollary, rather than proposition or theorem, is intrinsically subjective. Proposition B is a corollary of proposition A if B can readily be deduced from A or is self-evident from its proof, but the meaning of readily or self-evident varies depending upon the author and context. The importance of the corollary is often considered secondary to that of the initial theorem; B is unlikely to be termed a corollary if its mathematical consequences are as significant as those of A. Sometimes a corollary has a proof that explains the derivation; sometimes the derivation is considered to be self-evident.

In medicine, corollary sometimes refers to using older, more narrow spectrum antibiotics whenever possible. This is to avoid an increase in drug resistance.

- Peirce on corollarial and theorematic reasonings

Charles Sanders Peirce held that the most important division of kinds of deductive reasoning is that between corollarial and theorematic. He argued that, while finally all deduction depends in one way or another on mental experimentation on schemata or diagrams, still in corollarial deduction "it is only necessary to imagine any case in which the premisses are true in order to perceive immediately that the conclusion holds in that case," whereas theorematic deduction "is deduction in which it is necessary to experiment in the imagination upon the image of the premiss in order from the result of such experiment to make corollarial deductions to the truth of the conclusion." He held that corollarial deduction matches Aristotle's conception of direct demonstration, which Aristotle regarded as the only thoroughly satisfactory demonstration, while theorematic deduction (A) is the kind more prized by mathematicians, (B) is peculiar to mathematics,[1] and (C) involves in its course the introduction of a lemma or at least a definition uncontemplated in the thesis (the proposition that is to be proved); in remarkable cases that definition is of an abstraction that "ought to be supported by a proper postulate.".