Quetzalcoatl

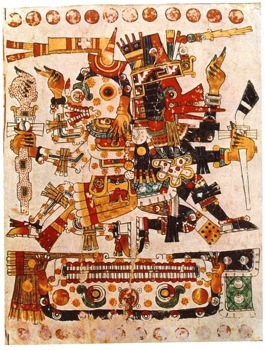

Quetzalcoatl (Template:Lang-nci Template:Pronounced) is an Aztec sky and creator god. The name is a combination of quetzal, a brightly colored Mesoamerican bird, and coatl, meaning serpent. The name was also taken on by various ancient leaders. Due to their cyclical view of time and the tendency of leaders to revise histories to support their rule, many events and attributes attributed to Quetzalcoatl are exceedingly difficult to separate from the political leaders that took this name on themselves.[1] Quetzalcoatl is often referred to as The Feathered Serpent and was connected to the planet Venus. He was also the patron god of the Aztec priesthood, of learning and knowledge.[2] Today Quetzalcoatl is arguably the best known Aztec deity, and is often thought to have been the principal Aztec god. However, Quetzalcoatl was one of several important gods in the Aztec pantheon along with the gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli.

Several other Mesoamerican cultures are known to have worshipped a feathered serpent god: At Teotihuacan the several monumental structures are adorned with images of a feathered serpent (Notably the so-called "Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl"[3]). Such imagery is also prominent at such sites as Chichen Itza and Tula. This has led scholars to conclude that the deity called Quetzalcoatl in the Nahuatl language was among the most important deities of Mesoamerica.[4]

The god Quetzalcoatl was sometimes conflated with Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl, a semi-legendary 10th century Toltec ruler.

Antecedents and origins

The Feathered Serpent deity was important in art and religion in most of Mesoamerica for close to 2,000 years, from the Pre-Classic era until the Spanish conquest. Civilizations worshiping the Feathered Serpent included the Mixtec and Aztec, who adopted it from the Toltec, who in turn had adopted it from the people of Teotihuacan, and the Maya.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Some Franciscans at this time held millennarian beliefs (Phelan 1956) and the natives taking the Spanish conquerors for gods was an idea that went well with this theology. Bernardino de Sahagún, who compiled the Florentine Codex, was also a Franciscan.

Some scholars still hold the view that the fall of the Aztec empire can in part be attributed to Moctezuma's belief in Cortés as the returning Quetzalcoatl, but most modern scholars see the "Quetzalcoatl/Cortés myth" as one of many myths about the Spanish conquest which have risen in the early post-conquest period.Template:Fact

However, it is interesting to note the resemblance of the Quetzacoatl legend with that of the myth of the Pahana held by the Hopis of northern Arizona. Scholars have described many similarities between the myths of the Aztecs and those of the American Southwest, and posit a common root.[5] The Hopi describe the Pahana as the "Lost White Brother," and they expected his eventual return from the east during which he would destroy the wicked and begin a new era of peace and prosperity. Hopi tradition maintains that they at first mistook the Spanish conquistadors as the Pahana when they arrived on the Hopi mesas in the 16th century.[6]<ref> Frank Waters. The Book of the Hopi, 252. According to Waters, "Tovar and his men were conducted to Oraibi. They were met by all the clan chiefs at Tawtoma, as prescribed by prophecy, where four lines of sacred meal were drawn. The Bear Clan leader stepped up to the barrier and extended his hand, palm up, to the leader of the white men. If he was indeed the true Pahana, the Hopis knew he would extend his own hand, palm down, and clasp the Bear Clan leader's hand to form the nakwach, the ancient symbol of brotherhood. Tovar instead curtly commanded one of his men to drop a gift into the Bear chief's hand, believing that the Indian wanted a present of some kind. Instantly all the Hopi chiefs knew that Pahana had forgotten the ancient agreement made between their peoples at the time of their separation. Nevertheless, the Spaniards were escorted up to Oraibi, fed and quartered, and the agreement explained to them. It was understood that when the two were finally reconciled, each would correct the other's laws and faults; they would live side by side and share in common all the riches of the land and join their faiths in one religion that would establish the truth of life in a spirit of universal brotherhood. The Spaniards did not understand, and having found no gold, they soon departed."

Notes

- Wirth, Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, Volume 11, Issue 1 2002 p.4

- Smith 2001 p. 213

- The Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl - Teotihuacan Tour

- Smith 2001 p. 219

- Spence, Lewis (2002). Atlantis in America, Book Tree. pp. p. 59. ISBN 1-8853-9597-3.

- Martínez & Mendieta.

- Susan E. James. Some Aspects of the Aztec Religion in the Hopi Kachina Cult, Journal of the Southwest (2000)

- Raymond Friday Locke. The Book of the Navajo, 139-140 (Hollaway House 2001).

- Frank Waters. The Book of the Hopi, 252. According to Waters, "Tovar and his men were conducted to Oraibi. They were met by all the clan chiefs at Tawtoma, as prescribed by prophecy, where four lines of sacred meal were drawn. The Bear Clan leader stepped up to the barrier and extended his hand, palm up, to the leader of the white men. If he was indeed the true Pahana, the Hopis knew he would extend his own hand, palm down, and clasp the Bear Clan leader's hand to form the nakwach, the ancient symbol of brotherhood. Tovar instead curtly commanded one of his men to drop a gift into the Bear chief's hand, believing that the Indian wanted a present of some kind. Instantly all the Hopi chiefs knew that Pahana had forgotten the ancient agreement made between their peoples at the time of their separation. Nevertheless, the Spaniards were escorted up to Oraibi, fed and quartered, and the agreement explained to them. It was understood that when the two were finally reconciled, each would correct the other's laws and faults; they would live side by side and share in common all the riches of the land and join their faiths in one religion that would establish the truth of life in a spirit of universal brotherhood. The Spaniards did not understand, and having found no gold, they soon departed."

References

See also

- Huitzilopochtli

- Tezcatlipoca

- Quetzalcoatlus, a pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous named after Quetzalcoatl

- ↑ Wirth, Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, Volume 11, Issue 1 2002 p.4

- ↑ Smith 2001 p. 213

- ↑ The Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl - Teotihuacan Tour

- ↑ Smith 2001 p. 219

- ↑ Susan E. James. Some Aspects of the Aztec Religion in the Hopi Kachina Cult, Journal of the Southwest (2000)

- ↑ Raymond Friday Locke. The Book of the Navajo, 139-140 (Hollaway House 2001).