Difference between revisions of "Codex"

(Created page with 'File:lighterstill.jpgright|frame ==Origin== (denoting a collection of statutes or set of rules): from Latin, literally ‘block of wood,’ la...') |

m (Text replacement - "http://" to "https://") |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Origin== | ==Origin== | ||

(denoting a collection of statutes or set of rules): from [[Latin]], literally ‘block of wood,’ later denoting a block split into leaves or tablets for [[writing]] on, hence a [[book]]. See also - [[code]]. | (denoting a collection of statutes or set of rules): from [[Latin]], literally ‘block of wood,’ later denoting a block split into leaves or tablets for [[writing]] on, hence a [[book]]. See also - [[code]]. | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/16th_century 16th Century] |

==Definitions== | ==Definitions== | ||

*1. an ancient [[manuscript]] [[text]] in [[book]] form. | *1. an ancient [[manuscript]] [[text]] in [[book]] form. | ||

*2. an official list of medicines, chemicals, etc. | *2. an official list of medicines, chemicals, etc. | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | A '''codex''' (Latin ''caudex'' for "trunk of a tree" or block of wood, book; plural ''codices'') is a book made up of a number of sheets of [[paper]], vellum, [[papyrus]], or similar, with hand-written [[content]], usually stacked and bound by fixing one edge and with covers thicker than the sheets, but sometimes continuous and folded [ | + | A '''codex''' (Latin ''caudex'' for "trunk of a tree" or block of wood, book; plural ''codices'') is a book made up of a number of sheets of [[paper]], vellum, [[papyrus]], or similar, with hand-written [[content]], usually stacked and bound by fixing one edge and with covers thicker than the sheets, but sometimes continuous and folded [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concertina concertina]-style. The alternative to paged codex format for a long document is the continuous scroll. Examples of folded codices are the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_codices Maya codices]. Sometimes the term is used for a book-style format, including modern printed [[books]] but excluding folded books. |

| − | Developed by the [[Romans]] from wooden [[writing]] tablets, its gradual replacement of the [[scroll]], the dominant form of book in the [[ancient]] world, has been termed the most important advance in the history of the book before the [ | + | Developed by the [[Romans]] from wooden [[writing]] tablets, its gradual replacement of the [[scroll]], the dominant form of book in the [[ancient]] world, has been termed the most important advance in the history of the book before the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Printing_press invention of printing]. The codex altogether [[transformed]] the shape of the book itself and offered a form that lasted for centuries. The spread of the codex is often associated with the rise of [[Christianity]], which adopted the format for the [[Bible]] early on. First described by the 1st-century AD Roman poet [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martial Martial], who praised its convenient use, the codex achieved numerical parity with the scroll around AD 300, and had completely replaced it throughout the now Christianised [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Roman_world Greco-Roman world] by the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/6th_century 6th century]. |

| − | The ''codex'' began to replace the [[scroll]] (or roll), almost as soon as it was invented. In Egypt by the fifth century, the codex outnumbered the scroll by ten to one based on surviving examples, and by the sixth century the scroll had almost vanished from use as a medium for [[literature]]. Although technically even modern paperbacks are codices, the term is now used only for [[manuscript]] (hand-written) books which were produced from Late antiquity until the [[Middle Ages]]. The [[scholarly]] [[study]] of these manuscripts from the point of view of the bookbinding craft is called [ | + | The ''codex'' began to replace the [[scroll]] (or roll), almost as soon as it was invented. In Egypt by the fifth century, the codex outnumbered the scroll by ten to one based on surviving examples, and by the sixth century the scroll had almost vanished from use as a medium for [[literature]]. Although technically even modern paperbacks are codices, the term is now used only for [[manuscript]] (hand-written) books which were produced from Late antiquity until the [[Middle Ages]]. The [[scholarly]] [[study]] of these manuscripts from the point of view of the bookbinding craft is called [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codicology codicology]; the [[study]] of [[ancient]] [[documents]] in general is called [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paleography paleography].[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex] |

[[Category: Languages and Literature]] | [[Category: Languages and Literature]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:41, 12 December 2020

Origin

(denoting a collection of statutes or set of rules): from Latin, literally ‘block of wood,’ later denoting a block split into leaves or tablets for writing on, hence a book. See also - code.

Definitions

- 1. an ancient manuscript text in book form.

- 2. an official list of medicines, chemicals, etc.

Description

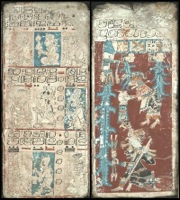

A codex (Latin caudex for "trunk of a tree" or block of wood, book; plural codices) is a book made up of a number of sheets of paper, vellum, papyrus, or similar, with hand-written content, usually stacked and bound by fixing one edge and with covers thicker than the sheets, but sometimes continuous and folded concertina-style. The alternative to paged codex format for a long document is the continuous scroll. Examples of folded codices are the Maya codices. Sometimes the term is used for a book-style format, including modern printed books but excluding folded books.

Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablets, its gradual replacement of the scroll, the dominant form of book in the ancient world, has been termed the most important advance in the history of the book before the invention of printing. The codex altogether transformed the shape of the book itself and offered a form that lasted for centuries. The spread of the codex is often associated with the rise of Christianity, which adopted the format for the Bible early on. First described by the 1st-century AD Roman poet Martial, who praised its convenient use, the codex achieved numerical parity with the scroll around AD 300, and had completely replaced it throughout the now Christianised Greco-Roman world by the 6th century.

The codex began to replace the scroll (or roll), almost as soon as it was invented. In Egypt by the fifth century, the codex outnumbered the scroll by ten to one based on surviving examples, and by the sixth century the scroll had almost vanished from use as a medium for literature. Although technically even modern paperbacks are codices, the term is now used only for manuscript (hand-written) books which were produced from Late antiquity until the Middle Ages. The scholarly study of these manuscripts from the point of view of the bookbinding craft is called codicology; the study of ancient documents in general is called paleography.[1]