Genesis

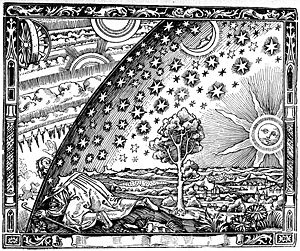

Genesis בְּרֵאשִׁית, Greek: Γένεσις, meaning "birth", "creation", "cause", "beginning", "source" or "origin") is the first book of the Torah, the Tanakh, and the Old Testament of the Bible. In Hebrew, it is called בראשית (B'reshit or Bərêšîth), after the first word of the text in Hebrew (meaning "in the beginning"). This is in line with the pattern of naming the other four books of the Pentateuch. As Jewish tradition considers it to have been written by Moses, it is sometimes also called The First Book of Moses.

Genesis recounts the creation of the world, including Adam and Eve and their fall from paradise. It follows the generations of various patriarchs and other figures: Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, and others. It establishes the Hebrew God, YHWH or Elohim, as the creator of the universe who has formed a special covenant with Abraham's descendents and his chosen people.

According to the documentary hypothesis, Genesis combines texts from different sources, but there is no consensus on the details.

Christians link many events and people in Genesis to Jesus Christ, who is said to be the "new Adam" with a new covenant. Muslims revere Adam, Abraham, and other men in Genesis, but they regard the book as corrupt.

Summary

Rolf Rendtorff's division of Genesis into a primeval history and Patriarchal cycles - Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph - is followed here for convenience in organising the summary.

Primeval history

"In the beginning God Genesis uses the words YHWH and Elohim (and El) for God; the combined form in Gen.2 and 3,YHWH Elohim, usually translated as "Template:LORD God", is unique to these two chapters. created the heavens and the earth.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Abram's wife Sarai, and his nephew Lot, the son of Abram's brother Haran, towards the land of Canaan. They settle in the city of Haran, where Terah dies.[1] God commands Abram, "Go from your country and your kindred and your father's house to the land that I will show you, and I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing.

I will bless those who bless you, and him who curses you I will curse; and by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves." So Abram and his people and flocks journey to the land of Canaan, where God appears to Abram and says, "To your descendants I will give this land.[2]

Abram is forced by famine to go into Egypt, where Pharaoh takes possession of his wife, the beautiful Sarai, whom Abram has misrepresented as his sister. God strikes the king and his house with plagues, so that he returns Sarai and expels Abram and all his people from Egypt.[3]

Abram returns to Canaan, and separates from Lot in order to put an end to disputes about pasturage. He gives Lot the valley of the Jordan, as far as Sodom, whose people "were wicked, great sinners against the Template:LORD." To Abram God says, "Lift up your eyes, and look ... for all the land which you see I will give to you and to your descendants for ever. I will make your descendants as the dust of the earth; so that if one can count the dust of the earth, your descendants also can be counted. Arise, walk through the length and the breadth of the land, for I will give it to you."[4]

Lot is taken prisoner during a war between the King of Shinar[5] and the King of Sodom and their allies, "four kings against five." Abram rescues Lot and is blessed by Melchizedek, king of Salem (the future Jerusalem) and "priest of God Most High". Abram refuses the King of Sodom's offer of the spoils of victory, saying: "I have sworn to the Template:LORD God Most High, maker of heaven and earth, that I would not take a thread or a sandal-thong or anything that is yours, lest you should say, `I have made Abram rich.'"[6]

God makes a covenant with Abram, promising that Abram's descendants shall be as numerous as the stars in the heavens, that they shall suffer oppression in a foreign land for four hundred years, but that they shall inherit the land "from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates."[7]

Sarai, being childless, tells Abram to take his Egyptian handmaiden, Hagar, as wife. Hagar falls pregnant with Ishmael,[8] and God appears to her to promise that the child will be "a wild ass of a man, his hand against every man and every man's hand against him," whose descendants "cannot be numbered."[9]

God makes a covenant with Abram: Abram will have a numerous progeny and the possession of the land of Canaan, and Abram's name is changed to "Abraham"[10] and that of Sarai to "Sarah," and circumcision of all males is instituted as an eternal sign of the covenant. Abraham asks of God that Ishmael "might live in Thy sight," but God replies that Sarah will bear a son, who will be named Isaac,[11] and that it is with Isaac and his descendants that the covenant will be established. "As for Ishmael, I have heard you; behold, I will bless him and make him fruitful and multiply him exceedingly; he shall be the father of twelve princes, and I will make him a great nation. But I will establish my covenant with Isaac."[12]

God appears again to Abraham. Three strangers[13] appear, and Abraham receives them hospitably. God tells him that Sarah will shortly bear a son, and Sarah, overhearing, laughs: "After I have grown old, and my husband is old, shall I have pleasure?"[14] God tells Abraham that he will punish Sodom, "because the outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah is great and their sin is very grave." The strangers depart. Abraham protests that it is not just "to slay the righteous with the wicked," and asks if the whole city can be spared if even ten righteous men are found there. God replies: "For the sake of ten I will not destroy it."[15]

The two[16] messengers are hospitably received by Lot. The men of Sodom surround the house and demand to have sexual relations with the strangers; Lot offers his two virgin daughters in place of the messengers, but the men refuse. Lot and his family are led out of Sodom, and Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed by fire-and-brimstone; but Lot's wife, looking back, is turned to a pillar of salt. Lot's daughters, fearing that they will not find husbands and that their line (Lot's line) will die out, make their father drunk and lie with him; their children become the ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites.[17]

Abraham represents Sarah as his sister before Abimelech,[18] king of Gerar. God visits a curse of barrenness upon Abimelech and his household, and warns the king that Sarah is Abraham's wife, not his sister. Abimelech restores Sarah to Abraham, loads them both with gifts, and sends them away.[19]

Isaac

Sarah gives birth to Isaac, saying, "God has made laughter for me, everyone who hears will laugh over me." At Sarah's insistence Ishmael and his mother Hagar are driven out into the wilderness. While Ishmael is near dying, an angel speaks to Hagar and promises that God will not forget them, but will make of Ishmael a great nation; "Then God opened her eyes, and she saw a well of water; and she went, and filled the skin with water, ... And God was with the lad, and he grew up..." Abraham enters into a covenant with Abimelech, who confirms his right to the well of Beer-sheba.[20]

God puts Abraham to the test by demanding the sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham obeys; but, as he is about to lay the knife upon his son, God restrains him, promising him numberless descendants.[21] On the death of Sarah, Abraham purchases Machpelah for a family tomb[22] and sends his servant to Mesopotamia, Nahor's home, to find among his relations a wife for Isaac; and Rebekah, Nahor's granddaughter, is chosen.[23] Other children are born to Abraham by another wife, Keturah, among whose descendants are the Midianites; and he dies in a prosperous old age and is buried in his tomb at Hebron.[24]

Jacob

Rebekah is barren, but Isaac prays to God and she gives birth to the twins Esau,[25] and Jacob.[26] While the twins were still in the womb God predicted that the two would be forever divided, and that the elder would serve the younger; and so it comes about that Esau the hunter sells his birthright to Jacob for a bowl of red porridge, and "therefore his name was called Edom."[27]

Isaac represents Rebekah as his sister before Abimelech, king of Gerar. Abimelech learns of the deception and is angered. Isaac is fortunate in all his undertakings in that country. His prosperity excites the jealousy of Abimelech, who sends him away; but the king sees that Isaac is blessed by God and makes a covenant with him at the well of Beer-sheba.[28]

Jacob deceives his father Isaac and obtains the blessing of prosperity[29] which should have been Esau's. Fearing Esau's anger he flees to Haran, the home of his mother's brother Laban.[30] Isaac, prohibiting Jacob from marrying a Canaanite woman, tells him to go and marry one of Laban's daughters. On the way, Jacob falls asleep on a stone and dreams of a ladder stretching from Heaven to Earth and thronged with angels, and God promises him prosperity and many descendants; and when he awakes Jacob sets the stone as a pillar[31] and names the place Bethel.[32]

Jacob hires himself to Laban on condition that, after having served for seven years as a herdsman, he shall marry the younger daughter, Rachel, with whom he is in love. At the end of this period Laban gives him the elder daughter, Leah, explaining that it is the custom to marry the elder before the younger; Jacob serves another seven years for Rachel, and has sons by his two wives and their two handmaidens, the ancestors of the tribes of Israel. Jacob then works another six years, deceiving Laban to increase his flocks at his uncle's expense, and gains great wealth in sheep, goats, camels, donkeys and slave-girls.

Jacob flees with his family and flocks from Laban; Laban pursues and catches him, but God warns Laban not to harm Jacob, and they are reconciled.[33] On approaching his home he is in fear of Esau, to whom he sends presents under the care of his servants, and then sends his wives and children away. "And Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day."[34] Neither Jacob nor the stranger can prevail, but the man touches Jacob's thigh and puts it out of joint, and pleads to be released before daybreak, but Jacob refuses to release the being until he agrees to give a blessing; the stranger then announces to Jacob that he shall bear the name "Israel", "for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed."[35] and is freed. "The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel,[36] limping because of his thigh."[37]

The meeting with Esau proves friendly, and the brothers are reconciled: "to see your face is like seeing the face of God," is Jacob's greeting. The brothers part, and Jacob settles near the city of Shechem.[38] Jacob's daughter Dinah goes out, and "Shechem the son of Hamor the Hivite, the prince of the land, saw her, he seized her and lay with her and humbled her".[39] Shechem asks Jacob for Dinah's hand in marriage, but the sons of Jacob deceive the men of Shechem and slaughter them and take captive their wives and children and loot the city. Jacob is angered that his sons have brought upon him the enmity of the Canaanites, but his sons say, "Should he treat our sister as a harlot?"[40]

Jacob goes up to Bethel; there "God said to him, Your name is Jacob; no longer shall your name be called Jacob, but Israel shall be your name. So his name was called Israel"; and Jacob sets up a stone pillar at the place, and names it Bethel. He goes up to his father Isaac at Hebron, and there Isaac dies and is buried.[41]

Genesis 36 is the Edomite King-list, describing the tribes and rulers of Edom, the nation of Esau.[42]

Joseph

Jacob makes a coat of many colours[43] for his favourite son, Joseph. Jacob's son Judah takes a Canaanite wife and has two sons, Er and Onan; Er dies, and his widow Tamar, disguised as a prostitute, tricks Judah into having a child by her (Er's brother Onan, who should have fathered the child, refused). She gives birth to twins, the elder of whom is Pharez, ancestor of the future royal house of David. Joseph's jealous brothers sell him to some Ishmaelites and show Jacob the coat, dipped in goat's blood, as proof that Joseph is dead. Meanwhile the Midianites[44] sell Joseph to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard,[45] but Potiphar's wife, unable to seduce Joseph, accuses him falsely and he is cast into prison.[46] Here he correctly interprets the dreams of two of his fellow prisoners, the king's butler and baker.[47] Joseph next interprets the dream of Pharaoh, of seven fat cattle and seven lean cattle, as meaning seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine, and advises Pharaoh to store grain during the good years. He is appointed second in the kingdom, and, in the ensuing famine, "all the earth came to Egypt to Joseph to buy grain, because the famine was severe over all the earth."[48]

Jacob sends his sons to Egypt to buy grain. The brothers appear before Joseph, who recognizes them, but does not reveal himself. After having proved them on this and on a second journey, and they having shown themselves so fearful and penitent that Judah even offers himself as a slave, Joseph reveals his identity, forgives his brothers the wrong they did him, and promises to settle in Egypt both them and his father[49] Jacob brings his whole family to Egypt, where Pharaoh assigns to them the land of Goshen.[50] Jacob receives Joseph's sons Ephraim and Manasseh among his own sons,[51] then calls his sons to his bedside and reveals their future to them.[52] Jacob dies and is interred in the family tomb at Machpelah (Hebron). Joseph lives to see his great-grandchildren, and on his death-bed he exhorts his brethren, if God should remember them and lead them out of the country, to take his bones with them. The book ends with Joseph's remains being "put in a coffin in Egypt."[53]

Composition

The oldest extant Masoretic (i.e. Hebrew) manuscripts of Genesis are the Aleppo Codex dated to ca. 920 AD, and the Westminster Leningrad Codex dated to 1008 AD. There are also fragments of unvocalized Hebrew Genesis texts preserved in some Dead Sea scrolls (2nd century BC to 1st century AD). According to tradition the Torah was translated into Greek (the Septuagint, or 70, from the traditional number of translators) in the 3rd century BC. The oldest Greek manuscripts include 2nd century BC fragments of Leviticus and Deuteronomy (Rahlfs nos. 801, 819, and 957), and 1st century BC fragments of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, and the Minor Prophets (Rahlfs nos. 802, 803, 805, 848, 942, and 943). Relatively complete manuscripts of the LXX (i.e.e, the Septuagint) include the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus of the 4th century and the Codex Alexandrinus of the 5th century - these are the oldest surviving nearly-complete manuscripts of the Old Testament in any language. There are minor variations between the Greek and Hebrew texts, and between the three oldest Greek texts.

For a number of reasons the traditional Jewish, and later Christian, belief that Genesis was written by Moses and inspired by God is no longer accepted by modern biblical scholars.[54] Contemporary academic debate centers instead on proposals which seek the origins of the Torah in the specific conditions of Jewish life and society in the 1st millennium BC. For much of the 20th century the field was dominated by the documentary hypothesis advanced by Julius Wellhausen in the late 19th century. This sees Genesis as a composite work assembled from various sources: the J text, named for its use of the term YHWH (JHWH in German) as the name of God; the E text, named for its characteristic usage of the term "Elohim" for God; and the P, or Priestly source. These texts were composed independently between 950 BC and 500 BC and underwent numerous processes of redaction, emerging in their current form in around 450 BC. A number of anomalous sources not traceable to any of the three major documents have been identified, notably Genesis 14 (the battle of Abraham and the "Kings of the East"), and the "Blessing of Jacob" contained in the Joseph narrative. One such work, the Book of Generations, was used by the Redactor (final editor of the Pentateuch) to provide the narrative framework for Genesis, ten occurrences of the toledot (Hebrew "generations") formula introducing as ten units of the book.[55]

The scholarly consensus which surrounded the Wellhausen hypothesis for much of the 20th century has collapsed since the 1970s.Template:Fact The theories currently being advanced can be divided into three models: revisions of Wellhausen's documentary model, of which Richard Elliot Friedman's is one of the better known;[56] fragmentary models, which see the Torah as composed from a multitude of small fragments rather than from large coherent source texts; and supplementary models, which sees in it the gradual accretion of material over many centuries and from many hands. Major contemporary scholars in this field include R. N. Whybray, who, drawing on techniques of literary analysis, does away with the documentary approach entirely and sees the Torah (and Genesis) as the work of a single author working around 500-450 BC; and John Van Seters, who retains much of the framework of the Wellhausen hypothesis but sees the Torah as the product of a process of gradual growth, with the final form not emerging until about 300 BC.[57]

Alongside these new approaches to the history of the text has come an increasing interest in the way the narratives tell their stories, with the theology of Genesis, rather than its origins, as its subject. "This move places a new emphasis on the narrative's purpose to shape audiences' perceptions of the world around them and to instruct them in how to live in this world and relate to its God."[58]

Themes

Cosmology

Genesis 1-11 "appears to be a reformatting of motifs and characters from four Mesopotamian myths, Adapa and the South Wind, Atrahasis, the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enuma Elish."[59] The Babylonian myths are inverted in the Hebrew retelling: for example, the Babylonian serpent-god Ningishzida is a friend of mankind who helps the human hero Adapa in his search for immortality, while Genesis' serpent is man's enemy, seeking to trick Adam out of the chance to attain immortality.[60] The inversions represent a rejection of the power of Babylon's gods in favour of the might of Yahweh; more than this, they replace the essentially optimistic worldview of the Mesopotamian mythos - "things were not nearly as good to begin with as they have become since" - with a worldview in which the world was created perfect but grew steadily worse, "until God finally had to do away with all mankind except for the pious Noah who would beget a new and better stock."[61]

The religion of the Patriarchs

In 1929 Albrecht Alt proposed that the Hebrews arrived in Canaan at different times and as different groups, each with its nameless "gods of the fathers," In time these gods were assimilated with the Canaanite El, and names such as "El, God of Israel" emerged. The "god of Abraham" then became identified with the "god of Isaac" and so on. Finally "Yahweh" was introduced in the Mosaic period. The authors of Genesis, living in a later period when Yahweh had become the only God, partly obscured and partly preserved this history in their attempt to demonstrate that the patriarchs shared their own monotheistic worship of Yahweh. According to Alt, the theology of the earliest period and of later fully-developed monotheistic Judaism were nevertheless identical: both Yahweh and the tribal gods revealed himself/themselves to the patriarchs, promised them descendants, and protected them in their wanderings; they in turn enjoyed a special relationship with their god, worshipped him, and established holy places in his honour.

In 1934 Julius Lewy, drawing on the recently discovered Ugarit texts, argued that the "god of Abraham" was not anonymous, but was probably El Shaddai, "El of the Mountain", El being identified with a mythical holy mountain. The name Shaddai, however, remains mysterious, and has also been identified with both a specific city and with a Hebrew root meaning "breast".[62] In 1962 Frank Moore Cross concluded that the name Yahweh developed as one of the many epithets of El: "El the creator, he who causes to be." For Cross the continuity between El and Yahweh explained how the other El-names could continue to be used in Genesis, and why Baal - in Canaanite mythology a rival to El who gradually took over the father-god's position - was regarded with such hostility.[63] More recently, Mark S. Smith has returned to the Ugarit texts to show how polytheism "was a feature of Israelite religion down through the end of the Iron Age and how monotheism emerged in the seventh and sixth centuries." [64]

In contrast to this picture of a Canaanite background to Genesis, Lloyd R. Bailey (1968) and E.L. Abel (1973) have suggested that Abraham worshipped Sin the Amorite moon-god of Harran, pointing, among other things, to Abraham's association with Harran and Ur, both centres of the cult of Sin, to the epithet "Father of the gods" applied to Sin (comparable to Abram's name, "Exalted Father") and to the close similarity between names associated with Abraham and with Sin: Sarah/Sarratu (Sin's wife); Milcah/Malkatu (Sin's daughter); and Terah/Ter (a name of Sin).[65] M. Haran has also distinguished between Canaanite and Patriarchal religion, pointing out that the Patriarchs never worship at existing shrines but build their own, fitting a semi-nomadic lifestyle. He also points to the invocation of Shaddai by Baalam and the identification of the Patriarchal God with the "sons of Eber" in Genesis 10:21 as evidence that their god was not originally Canaanite. Gordon Wenham has pointed out that Il/El is a well-known member of the third-millennium Mesopotamian pantheon, concluding: "Whether El was ever identified with the moon god is uncertain. To judge from the names of Abraham's relations and the cult of his home town, his ancestors at least were moon-god worshippers. Whether he continued to honour this god identifying him with El, or converted to El, is unclear."[66]

Covenants

The covenants are a major theme in Genesis, "yet it has long been recognised that many of the promises are not original parts of the stories in which they are found."[67] Otto Eissfeldt, an early scholar of the Ugarit texts, recognised that in Ugarit the promise of a son was given to kings together with promises of blessing and numerous descendants, a clear parallel to the pattern of Genesis. Claus Westermann, (1964 and 1976), analysing the Genesis covenants in the light of Ugarit and Icelandic sagas, came to the conclusion that the Patriarchal stories were usually lacking any promises in their original form. Westermann saw the promise of a son in Genesis 16:11 and 18:1-15 as genuine, as well as the promise of land behind 15:7-21 and 28:13-15; the rest he saw as representing later editors.[68] Rolf Rendtorff accepts Westermann's thesis that the Patriarchal stories were originally independent, and suggests that the promises were added to link the stories of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob into cycles which grew through a process of gradual accretion into the final book. John Van Seters, in contrast, sees Genesis as a late and unified composition, from which it is impossible to excise the Covenants without doing damage to the overall narrative.[69]

Genesis and subsequent Abrahamic tradition

Christianity

The early Church, with its Jewish roots, assumed an authoritative nature for Genesis and based its own emerging theology on this and other Jewish holy texts. The author of the gospel of John paraphrased Genesis 1 to personify the eternal logos (Greek λογος, "reason", "word", "speech"): "In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God." This passage marks the first definitive emergence of the distinctive Christian concept of the Trinity, and thus of Christianity's emerging break with Judaism in the late 1st century. The serpent of Eden became Satan, and Genesis 3:15, "He shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel," became the Protevangelium, the "First Gospel", predicting the coming of the Messiah who would be victorious over evil and Satan; Jesus was interpreted as the "new Adam" who would redeem mankind from the sin of Eden, and the Ark of Noah became symbolic of the Church itself, offering salvation through the waters of baptism. The Abrahamic covenant was reinterpreted to further underline the separation from Judaism: God's promise of a chosen people had passed from the children of Abraham, who had rejected Jesus, and was bestowed upon all those who accepted the new Covenant between God, in the divine person of his Son, and his Church.

Not only the general theology of Christianity but also specific narrative details of the new faith drew on the authority of Genesis: thus the three angelic strangers who visit Abraham to announce the birth of Isaac are paralleled by the (inferred) three magi who visit the infant Jesus; and the tale of Joseph in Egypt is echoed by the Holy Family's flight into Egypt.

Islam

Template:Main Many of the stories from Genesis are retold in the Qur'an, with frequent variations. The Qur'an emphasises the moral stature of the Prophets; stories such as the drunkenness of Lot therefore find no place in it. While Islam accepts the Torah in principle, the view of Islamic scholarship is that the revelation given to earlier times had become corrupted, and that the only valid text is that revealed by God to His Prophet Mohammed. The Qur'an, the final revelation, contains the essence of all previous revelations, including the Torah.

See also

- Enûma Elish

- Dating the Bible

- Tanakh

- The Bible and history

- The Hebrew Bible

- Origin belief

- Weekly Torah portions in Genesis: Bereishit, Noach, Lech-Lecha, Vayeira, Chayei Sarah, Toledot, Vayetze, Vayishlach, Vayeshev, Miketz, Vayigash, Vayechi

- Wife-sister narratives in Genesis

- Kabbalah

- Framework interpretation (Genesis)

- Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

- Genesis Rabba

- Creation according to Genesis

Notes

Further reading

- Umberto Cassuto, From Noah to Abraham. Eisenbrauns, 1984. ISBN 965-223-540-7 (A scholarly Jewish commentary.)

- Isaac M. Kikawada & Arthur Quinn, Before Abraham was – The Unity of Genesis 1-11. Nashville, Tenn., 1985. (A challenge to the Documentary Hypothesis.)

- Nehama Leibowitz, New Studies in Bereshit, Genesis. Jerusalem: Hemed Press, 1995. (A scholarly Jewish commentary employing traditional sources.)

- Henry M. Morris, The Genesis Record: A Scientific and Devotional Commentary on the Book of Beginnings. Baker Books, 1981. ISBN 0-8010-6004-4 (A creationist Christian commentary.)

- Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI), In the Beginning. Edinburgh, 1995. (A Catholic understanding of the story of Creation and Fall.)

- Jean-Marc Rouvière, Brèves méditations sur la création du monde. L'Harmattan Paris, 2006.

- Nahum M. Sarna, Understanding Genesis. New York: Schocken Press, 1966. (A scholarly Jewish treatment, strong on historical perspective.)

- Nahum M. Sarna, The JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989. (A mainstream Jewish commentary.)

- E. A. Speiser, Genesis, The Anchor Bible. Volume 1. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1964. (A translation with scholarly commentary and philological notes by a noted Semitic scholar. The series is written for laypeople and specialists alike.)

- Bruce Vawter, On Genesis: A New Reading. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1977. (An introduction to Genesis by a fine Catholic scholar. Genesis was Vawter's hobby.)

- Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg, The Beginning of Desire: Reflections on Genesis. New York: Doubleday, 1995. (A scholarly Jewish commentary employing traditional sources.)

External links

Online texts and translations of Genesis

- Westminster-Leningrad codex

- Aleppo Codex

- בראשית Bereishit - Genesis (Hebrew - English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- Bereshit with commentary in Hebrew

- RSV Genesis

Other sites

- A detailed chart of Adam's descendants according to Genesis

- "what happens when an ignorant person actually reads the book on which his religion is based", Slate.com deputy editor David Plotz' multipart diary

- "Genesis 27-36: The purpose of the various forms of repetition in the Beth-el accounts "

- ↑ Genesis 11.

- ↑ Genesis 12.

- ↑ Genesis 12.

- ↑ Genesis 13.

- ↑ An inexact location, but roughly equivalent to the lands of the Tigris and Euphrates.

- ↑ Genesis 14.

- ↑ Genesis 15. The "river of Egypt", traditionally identified not with the Nile but with Wadi el Arish in the Sinai, and the Euphrates, represent the supposed bounds of Israel at its height under Solomon.

- ↑ Hebrew Yishmael, "God will hear".

- ↑ Genesis 16.

- ↑ The name Abraham has no meaning in Hebrew. It is traditionally supposed to signify "Father of Multitudes," although the Hebrew for this would be "Abhamon".

- ↑ Hebrew Yitzhak, "he laughed," sometimes rendered as "he rejoiced" - three explanations of the name are given, the first in this chapter where Abraham laughs when told that Sarah will bear a son.

- ↑ Genesis 17.

- ↑ Often translated as "angels", but the Hebrew refers to men.

- ↑ The second explanation of the name Isaac - in the first, at chapter 17, it is Abraham who laughs.

- ↑ Genesis 18. Abraham's intercession on behalf of the people of Sodom is the foundation of the important Jewish tradition of righteousness.

- ↑ Genesis 18 describes three messengers, Genesis 19 two. The traditional gloss is that God was one of the three who came to Abraham, and stayed with him while the other two went on to Sodom.

- ↑ Genesis 19.

- ↑ Literally, "father-king", apparently a title.

- ↑ Genesis 20.

- ↑ Genesis 21.

- ↑ Genesis 22.

- ↑ Genesis 23.

- ↑ Genesis 24.

- ↑ Genesis 25.

- ↑ Hebrew Esav, "made" or "completed".

- ↑ Hebrew Yaakov, from a root meaning "crooked, bent", usually interpreted as meaning "heel" - according to the narrative he was born second, holding Esau's heel. The precise meaning is unclear.

- ↑ Edom, literally "red". Genesis 25.

- ↑ Genesis 26.

- ↑ "May God give you of the dew of heaven, and of the fatness of the earth, and plenty of grain and wine. 29: Let peoples serve you, and nations bow down to you. Be lord over your brothers, and may your mother's sons bow down to you. Cursed be every one who curses you, and blessed be every one who blesses you!" (Genesis 27:28-29)

- ↑ Genesis 27.

- ↑ Traditionally the place where this pillar is erected is identified as the site of the Holy of Holies within the Jewish Temple at Jerusalem.

- ↑ Genesis 28. The name Bethel in Hebrew and related West Semitic languages means "House of El;" in later Jewish tradition the name was taken to mean "House of God."

- ↑ Genesis 31.

- ↑ Literally, "a stranger," traditionally interpreted as an angel or as God.

- ↑ Hebrew Yisrael, "He will struggle with God;" but the second part of the quoted verse can be translated as: "for you have become great (sar) before God and men," implying that "Israel" means "He will be great (sar) before God."

- ↑ Penuel or Peniel, literally "Face of God" - the sentence connects the mysterious stranger and the following passage about the meting with Esau.

- ↑ Genesis 32.

- ↑ Genesis 33.

- ↑ This passage is traditionally taken to mean that Shechem raped rather than seduced Dinah, but the text is not conclusive.

- ↑ Genesis 34.

- ↑ Genesis 35.

- ↑ Genesis 36.

- ↑ Hebrew Kethoneth passim This is traditionally translated as "coat of many colours", but can also mean long sleeves, or embroidered. Whatever translation is chosen, it means a royal garment.

- ↑ The merchants are described first as Ishmaelites and later as Midianites. There have been many attempts to reconcile the discrepancy.

- ↑ Genesis 37.

- ↑ Genesis 39.

- ↑ Genesis 40.

- ↑ Genesis 41.

- ↑ Genesis 42-45

- ↑ Genesis 46-47

- ↑ Genesis 48

- ↑ Genesis 49

- ↑ Genesis 50. The Book of Joshua describes the later burial of Joseph's bones in Shechem following the Exodus from Egypt.

- ↑ See this site for an outline of the Mosaic authorship tradition.

- ↑ See Frank Moore Cross, The Priestly Work, in "Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic", 1973. The toledot are:

- The generations of the heavens and the earth (2:4).

- The generations of Adam (5:1).

- The generations of Noah (6:9).

- The generations of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the sons of Noah (10:1).

- The generations of Shem (11:10).

- The generations of Terah (11:27).

- The generations of Ishmael (25:12).

- The generations of Isaac (25:19).

- The generations of Esau (36:1, 9).

- The generations of Jacob (37:2).

- ↑ Richard Elliot Friedman, "The Bible with Sources Revealed", 2003 - see Bibliography section.

- ↑ For an overview of current critical theories on the origins of the Pentateuch, see Source Analysis: Revisions and Alternatives. For a more detailed treatment, see "An overlooked message: the critique of kings and affirmation of equality in the primeval history" from Biblical Theology Bulletin, Winter 2006.

- ↑ "What's New in Interpreting Genesis" - a review of some new writings on theology and Genesis, 1995.

- ↑ "Genesis' Genesis, The Hebrew Transformation of the Ancient Near Eastern Myths and Their Motifs.

- ↑ "Genesis' Genesis, The Hebrew Transformation of the Ancient Near Eastern Myths and Their Motifs. See the end of the article for a full list of the inversions in Genesis 1-11.

- ↑ T. Jacobson, "The Eridu Genesis", JBL 100, 1981, pp.529, quoted in Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch", 2003, p.17.

- ↑ See Biblical Studies Org. and David Biale, "The God With Breasts: El Shaddai in the Bible, 1982.

- ↑ Frank Moore Cross, "Yahweh and the God of the Patriarchs, 1962 and 1973.

- ↑ Mark S. Smith, "The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts", 2002. Review of "Origins of Biblical Monotheism", Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, Vol. 4 (2002-2003).

- ↑ Lloyd Bailey, "Israelite El Sadday and Amorite Bel Sade" and E.L. Abel, "The Nature of the Patriarchal God El Sadday".

- ↑ Gordon J. Wenham, "The Religion of the Patriarchs"

- ↑ J.A. Emmerton, "The Origin of the Promises to the Patriarchs in the Older Sources of the Book of Genesis".

- ↑ Westermann distinguished four types of promise: a son; descendents; blessing; land. He regarded promises as early if they were not combined and if they were intrinsic to the narrative.

- ↑ Summarised from "The Patriarchs: History and Religion".