Violence

Violence is the expression of physical force against self or other, compelling action against one's will on pain of being hurt.[1][2][3], Variant uses of the term refer to the destruction of non-living objects (property damage). Worldwide, violence is used as a tool of manipulation and also is an area of concern for law and culture who take attempts to supress and stop it. Violence can take many forms anywhere from mere hitting between two humans where there can be just mere bodily harm, to war and genocide where millions may die as a result.

Law

One of the main functions of law is to regulate violence.

Sociologist Max Weber stated that state power is the monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force on a specific territory. Law enforcement is the main means of regulating nonmilitary violence in society. Governments regulate the use of violence through legal systems governing individuals and political authorities, including the police and military. Most societies condone some amount of police violence to maintain the status quo and enforce laws.

However, German political theorist Hannah Arendt noted: "Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate ... Its justification loses in plausibility the farther its intended end recedes into the future. No one questions the use of violence in self-defence, because the danger is not only clear but also present, and the end justifying the means is immediate". In the 20th century in acts of democide governments may have killed more than 260 million of their own people through police brutality, execution, massacre, slave labor camps, and through sometimes intentional famine.[4] Atlas - Wars and Democide of the Twentieth Century

Violent acts that are not carried out by the military or police and that are not in self-defence are usually classified as crimes, although not all crimes are violent crimes. Damage to property is classified as violent crime in some jurisdictions but not in others. It is usually considered a less serious offense unless the damage injures, or potentially could injure, others. Unpremeditated or small-scale acts of random violence or coordinated violence by unsanctioned private groups usually are prosecuted. While most societies condone the killing of animals for food and sport, increasingly they have adopted more laws against animal cruelty.

Religious and political ideology

Religious and political ideologies have been the cause of interpersonal violence, and violent riots, political repression, ethnic cleansing and genocide throughout history. Ideologues often falsely accuse others of violence, such as the ancient blood libel against Jews, the medieval accusations of casting witchcraft spells against women, caricatures of black men as “violent brutes” that helped excuse the late nineteenth century Jim Crow laws in the United States,[5] and modern accusations of satanic ritual abuse against day care center owners and others. [6]

Both supporters and opponents of the twenty-first century War on Terrorism regard it largely as an ideological and religious war.[7] [8] [9]

Vittorio Bufacchi describes two different modern concepts of violence, one the “minimalist conception” of violence as an intentional act of excessive or destructive force, the other the “comprehensive conception” which includes violations of rights, including a long list of human needs. These concepts are reflected in conflicts between “left wing” anti-capitalists and “right wing’” pro-capitalists.

Anti-capitalists assert that capitalism is violent. They believe private property, trade, interest and profit survive only because police violence defends them and that capitalist economies need war to expand. [10] Capitalism explained Many contest calling any form of property damage violent.[11][12] [13] Similarly, many anti-capitalists lambast what they call structural violence which denotes a form of violence in which social institutions kill people slowly by preventing them from meeting their basic needs, often leading further to social conflict and violence.

Supporters of capitalism are wary of a wide definition of violence that requires the state and its violent enforcement agencies to fulfill all needs denied by structural violence. However, unlike those critics who support state capitalism,[14] free market supporters argue that it is violently enforced state laws intervening in markets which cause many of the problems anti-capitalists attribute to structural violence.[15]

Throughout history, most religions and individuals like Mahatma Gandhi have preached that humans are capable of eliminating individual violence and organizing societies through purely nonviolent means. Gandhi himself once wrote: “A society organized and run on the basis of complete non-violence would be the purest anarchy.” Modern political ideologies which espouse similar views include pacifist varieties of voluntarism, mutualism, anarchism and libertarianism.

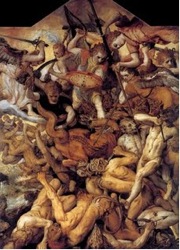

War

War is a state of prolonged violence, large-scale conflict involving two or more groups of people, usually under the auspices of government. War is fought as a means of resolving territorial and other conflicts, as war of aggression to conquer territory or loot resources, in national self-defense, or to suppress attempts of part of the nation to secede from it.

Since the Industrial Revolution, the lethality of modern warfare has steadily grown. World War I casualties were over 40 million and World War II casualties were over 70 million.

Nevertheless, some hold the actual deaths from war have decreased compared to past centuries. In War Before Civilization, Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor at the University of Illinois, calculates that 87% of tribal societies were at war more than once per year, and some 65% of them were fighting continuously. The attrition rate of numerous close-quarter clashes, which characterize endemic warfare, produces casualty rates of up to 60%, compared to 1% of the combatants as is typical in modern warfare.[16]. Stephen Pinker agrees, writing that “in tribal violence, the clashes are more frequent, the percentage of men in the population who fight is greater, and the rates of death per battle are higher.

Jared Diamond in his award-winning books, Guns, Germs and Steel and The Third Chimpanzee provides sociological and anthropological evidence for the rise of large scale warfare as a result of advances in technology and city-states. The rise of agriculture provided a significant increase in the number of individuals that a region could sustain over hunter-gatherer societies, allowing for development of specialized classes such as soldiers, or weapons manufacturers. On the other hand, tribal conflicts in hunter-gatherer societies tend to result in wholesale slaughter of the opposition (other than perhaps females of child-bearing years) instead of territorial conquest or slavery, presumably as hunter-gatherer numbers could not sustain empire-building.

Entertainment

Both in fabrication and reality, violence is integrated into sporting events. This was very prevalent in Greece during the olympic games where Wrestling and Boxing was an entertaining sport, many people would fight to the death in these spectacles. An even more well known and notorious example is in Rome where Gladiators would fight animals and other Gladiators until someone was killed in the process, also in theatre a scene that called for a person to be killed in a violent manner, they would indeed kill an actor or a step-in. In Asia, martial arts became both a sport and a way of life for followers. Currently, Boxing, Professional Wrestling, Various Martial Arts are a set of violent sports that have become profitable forms of entertainment worldwide.

Government censorship has sometimes addressed such violence in media but generally governments have relied heavily upon commercial interests to "self-regulate" their practice, by way of violence ratings. [17] Violent content continues to be a central component of video game revenues though critics argue that violence in games hardens children to unethical acts. Violence in Media Entertainment; [18]

Quote

Competition is essential to social progress, but competition, unregulated, breeds violence. In current society, competition is slowly displacing war in that it determines the individual's place in industry, as well as decreeing the survival of the industries themselves. (Murder and war differ in their status before the mores, murder having been outlawed since the early days of society, while war has never yet been outlawed by mankind as a whole.) The ideal state undertakes to regulate social conduct only enough to take violence out of individual competition and to prevent unfairness in personal initiative. Here is a great problem in statehood: How can you guarantee peace and quiet in industry, pay the taxes to support state power, and at the same time prevent taxation from handicapping industry and keep the state from becoming parasitical or tyrannical?[19]

References

- Merriam-webster Dictionary Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- Oford English Dictionary Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- American Heritage Dictionary, Violence, Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- The Neurobiology of Violence, An Update, Journal of Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 11:3, Summer 1999.

- Heather Whipps, Peace or War? How early humans behaved, LiveScience.Com, March 16, 2006.

- Rowan, John (1978). The Structured Crowd. Davis-Poynter..

- Cindy Fazzi, Debunking the "killer ape" myth, Dispute Resolution Journal, May-July 2002.

- Gilligan, James (1996). Violence: Our Deadly Epidemic and Its Causes. Putnam Adult. ISBN 0-399-13979-6 .

- Emotional Competency; Dr. Michael Obsatz,From Shame-Based Masculinity to Holistic Manhood, Robin Morgan, The Demon Lover On the Sexuality of Terrorism, W.W. Norton, 1989, Chapter 5.

- Stephen Pinker, The History of Violence, The New Republic, March 19, 2007.

- First, M.B., Bell, C.C., Cuthbert, B., Krystal, J.H., Malison, R., Offord, D.R., Riess, D., Shea, T., Widiger, T., Wisner, K.L., Personality Disorders and Relational Disorders, pp.164,166 Chapter 4 of Kupfer, D.J., First, M.B., & Regier, D.A. A Research Agenda For DSM-V. Published by American Psychiatric Association (2002)

- First, M.B., Bell, C.C., Cuthbert, B., Krystal, J.H., Malison, R., Offord, D.R., Riess, D., Shea, T., Widiger, T., Wisner, K.L., Personality Disorders and Relational Disorders, p.163, Chapter 4 of Kupfer, D.J., First, M.B., & Regier, D.A. A Research Agenda For DSM-V. Published by American Psychiatric Association (2002)

- First, M.B., Bell, C.C., Cuthbert, B., Krystal, J.H., Malison, R., Offord, D.R., Riess, D., Shea, T., Widiger, T., Wisner, K.L., Personality Disorders and Relational Disorders, p.166, Chapter 4 of Kupfer, D.J., First, M.B., & Regier, D.A. A Research Agenda For DSM-V. Published by American Psychiatric Association (2002)

- First, M.B., Bell, C.C., Cuthbert, B., Krystal, J.H., Malison, R., Offord, D.R., Riess, D., Shea, T., Widiger, T., Wisner, K.L., Personality Disorders and Relational Disorders, p.167,168 Chapter 4 of Kupfer, D.J., First, M.B., & Regier, D.A. A Research Agenda For DSM-V. Published by American Psychiatric Association (2002)

- [Hall RCW, Zisook S. Paradoxical Reactions to Benzodiazepines. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1981; 11: 99S-104S}

- Lader M, Morton S. Benzodiazepine Problems. British Journal of Addiction 1991; 86: 823-828}

- Benzodiazepines: Paradoxical Reactions & Long-Term Side-Effects

- Hansson O, Tonnby B. [Serious Psychological Symptoms Caused by Clonazepam.] Läkartidningen 1976; 73: 1210-1211.

- see: Joseph (Yossi) E. David, The One who is More Violent Prevails - Law and Violence from a Talmudic Legal Perspective, Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2006

- Arendt, Hannah sfdhxvczgrsdfcxzrfergSDS n Violence. Harvest Book. p. 52. .

- Twentieth Century Democide; [https://users.erols.com/mwhite28/war-1900.htm Atlas - Wars and Democide of the Twentieth Century.

- "Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook" (PDF). Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2004. https://www.fbi.gov/ucr/handbook/ucrhandbook04.pdf. .

- Review of book “War Before Civilization” by Lawrence H. Keeley, July, 2004.

- Stephen Pinker.

- "Doctrinal War: Religion and Ideology in International Conflict," in Bruce Kuklick (advisory ed.), The Monist: The Foundations of International Order, Vol. 89, No. 2 (April 2006), p. 46.

- The Brute Caricature, Ferris State University Museum of Racist Memorabilia.

- 42 M.V.M.O. Court Cases with Allegations of Multiple Sexual And Physical Abuse of Children.

- John Edwards' 'Bumper Sticker' Complaint Not So Off the Mark, New Memo Shows; Richard Clarke, Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror, Free Press; 2004; Michael Scheuer, Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terror, Potomac Books Inc., June, 2004; Robert Fisk, The Great War for Civilisation - The Conquest of the Middle East, Fourth Estate, London, October 2005; Leon Hadar, The Green Peril: Creating the Islamic Fundamentalist Threat, August 27, 1992; Michelle Malkin, Islamo-Fascism Awareness Week kicks off, October 22, 2007; John L. Esposito, Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam, Oxford University Press, USA, September 2003.

- Vittoriio Bufacchi, Two Concepts of Violence, Political Studies Review, April 2005, Volume 3, Issue 2, Page 193-204.

- Michael Albert Life After Capitalism - And Now Too. Zmag.org, December 10, 2004; Capitalism explained .

- L.A. Kaufman, Who were those masked anarchists in Seattle?, December 10, 1999; Eco-Warrior Celebrates Another Year Behind Society's Bars of Ignorance; Liz Highleyman, The Global Justice Movement.

- Bruce Bawer, The Peace Racket, September 7, 2007.

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, From the Economics of Laissez Faire to The Ethics of Libertarianism.

- Bharatan Kumarappa, Editor, "For Pacifists," by M.K. Gandhi, Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, India, 1949.

Sources

- Walter Benjamin's Critique of Violence

- Arno Gruen psychoanalyst who has written extensively on the origins of violence

- Flannery, D.J., Vazsonyi, A.T.& Waldman, I.D. (Eds.) (2007). The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression. Cambridge University Press, NY.

- Nazaretyan, A.P. (2007). Violence and Non-Violence at Different Stages of World History: A view from the hypothesis of techno-humanitarian balance. In: History & Mathematics. Moscow: KomKniga/URSS. P.127-148. ISBN 9785484010011.

- Gad Barzilai.(2003). Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472113151.

External links

- Information on James W. Prescott's work

- 1986 Seville Statement on Violence

- Introduction and Updated Information on the Seville Statement on Violence

- The Meanings of Violence and the Violence of Meanings Intercultural discussions on violence

- Institute on Violence, Abuse and Trauma

- Violence Prevention Institute

- Text of Dom Helder Camara's classic 1971 "Spiral of Violence"

- Boys Equally At Risk For Partner Violence

- Violent Youth